Wednesday, December 31, 2008

Using Studio’s Title Editor

Making effective titles

When using titles in your movies, you should follow some basic guidelines to make them more effective. After all, funny or informative titles don’t do much good if your audience can’t read them. Follow these general rules when creating titles for your movies:

When using titles in your movies, you should follow some basic guidelines to make them more effective. After all, funny or informative titles don’t do much good if your audience can’t read them. Follow these general rules when creating titles for your movies:- Less is more. Try to keep your titles as brief and simple as possible.

- White on black looks best. When you read words on paper, black letters on white paper are easier to read. This rule does not carry over to video, however. In video images, light characters over a dark background are usually easier to read. An exception would be if you already have a relatively light background. But what if I want to put that same title near the top of the screen instead? The dark-colored title won’t work as well at the top of the screen because trees in the background will make it harder to read. As an alternative, I can create a small, dark background shape behind lighter colored text. (I’ll show you how to control title colors and styles in the next couple of sections.) Video displays such as TVs and computer monitors generate images using light. (You can think of a TV screen as a big light bulb.) Because TV displays emit light, full-screen titles almost never have black text on a white screen. Most people find staring at a mostly white TV screen about as unpleasant as staring at a lit light bulb: If you watch viewers look at a white TV screen, you may even see them squint. Squinting is bad, so stick to the convention of light words over a dark background whenever possible.

- Avoid very thin lines. In an interlaced display —such as a TV — every other horizontal resolution line of the video image is drawn in a separate pass or field. If the video image includes very thin lines — especially lines that are only one pixel thick — interlacing could cause the lines to flicker noticeably, giving your viewers a migraine headache in short order. To avoid this, choose fonts that have thicker lines. For smaller characters, avoid serif fonts such as Times New Roman. Serifs (the extra strokes at the ends of characters in some fonts, such as the one you’re reading right now) often have very thin lines that flicker on an interlaced video display.

- Think big. Remember that the resolution on your computer screen is a lot finer than what you get on a typical TV screen. Also, TV viewers typically watch video from longer distances than do computer users — say, across the room while plopped on the sofa, compared to sitting just a few inches away in an office chair. This means the words that look pleasant and readable on your computer monitor may be tiny and unintelligible if your movie is output to tape for TV viewing. Never be afraid to increase the size of your titles.

- Think safety. Most TVs suffer from a malady called overscan, which is what happens when some of the video image is cut off at the edges of the screen. You can think of TVs as being kind of like most computer printers. Most TVs can’t display the far edges of the video image, just as most printers can’t print all the way to the very edges of the paper. When you’re working on a word processing document, your page has margins to account for the shortcomings of printers as well as to make the page more readable. The same applies to video images, which have title safe margins. To ensure that your titles show up on-screen and are not cut off at the edges, make sure your titles remain within this margin (also sometimes called the title safe boundary). Apple iMovie doesn’t show these margins on-screen; instead, it automatically keeps your titles inside the margins. If you know your movie will be viewed only on computer screens, place a check mark next to the QT Margins option in the Titles window. This places the margins closer to the edge of the screen.

- The margins are displayed on-screen and you have to remember to keep your titles inside them. The margins appear in the Title Editor window as red dotted lines.

- Play, play, play. I cannot stress enough the importance of previewing your titles, especially overlays. Play your timeline after adding titles to see how they look. Make sure the title is readable, positioned well onscreen, and visible long enough to be read. If possible, preview the titles on an external video monitor.

Tuesday, December 16, 2008

Creating titles for your movies

It’s easy to think of titles as just words on the screen. But think of the effects, both forceful and subtle, that well-designed titles can have. Consider the Star Wars movies, which all begin with a black screen and the phrase, “A long time ago, in a galaxy far, far away . . .” The simple title screen quickly and effectively sets the tone and tells the audience that the story is beginning. And then, of course, you get those scrolling words that float three-dimensionally off into space, immediately after that first title screen. A story floating through space is far more interesting than white text scrolling from the bottom to top of the screen, don’t you think?

Titles can generally be put into two basic categories: Full-screen and overlays. Full-screen titles are most often used at the beginning and end of a movie, where the title appears over a background image or a solid color (such as a plain black screen). The full-screen title functions as its own element in the movie, as does any video clip. An overlay title makes words appear right over a video image

Giving Credit with Titles

In their rush to get to the pictures, folks who are new to video editing often overlook the importance of titles. Titles — the words that appear on-screen during a movie — are critically important in many different kinds of projects. Titles tell your audience the name of your movie, who made it, who starred in it, who paid for it, and who baked cookies for the cast. Titles can also clue the audience in to vital details — where the story takes place, what time it is, even what year it is — with minimum fuss. And of course, titles can reveal what the characters are saying if they’re speaking a different language. Virtually all video-editing programs include tools to help you create titles.

Adjusting transitions in Studio

Adjusting transitions in Pinnacle Studio works a lot like adjusting regular video clips. To modify a transition, here’s the drill:

- Double-click the transition in the timeline. The Clip Properties window appears above the timeline.

- Adjust the Duration of the transition in the upper-right corner of the window by clicking the up or down arrows next to the Duration field at the top of the Clip Properties window.

- If you’re working with sample clips, change the duration to 15 frames.

Modifying iMovie transitions

The iMovie transition window doesn’t just provide a place to store transitions; it also allows you to control them. To adjust the length of a transition, follow these steps:

- Click the transition in the timeline to select it.

- Adjust the Speed slider in the transitions window. If you’re working with sample clips, adjust the transition between Scene 1 and Scene 2 down so it’s only 15 frames long. The length of the transition will be shown in the preview window.

- Click Update in the transitions window to update the length of the transition in the timeline.

- Click the Play button under the preview window to preview your results.

Adjusting transitions

Sometimes a two-second transition is too long — or not long enough. When applied to the sample clips Scene 1 and Scene 2, a two-second dissolve really is too long because it obscures a spectacular crash at the end of Scene 1. The next two sections show you how to adjust the length of transitions and make other changes where possible.

Sunday, November 30, 2008

Adding a transition to the timeline

Adding a transition to a project is pretty easy and works the same way in almost every video-editing program available. For now, add a simple dissolve (also called a fade) transition to a project. If your editing program currently shows the storyboard for your project, switch to the timeline. Next, click-and-drag the Dissolve (in Pinnacle Studio) or Cross Dissolve (in iMovie) transition from the list of transitions and drop it between two clips on the timeline. Drop the transition between the first two scenes. The transition will now appear in the timeline between the clips.

The appearance of the transition will vary slightly depending on the editing program you are using. Pinnacle Studio displays the transition as a clip in the Timeline. Apple iMovie, on the other hand, uses a special transition icon that overlaps the adjacent clips, when you first apply a transition in iMovie, the program must render the transition before it can be viewed. Basically it’s a process that allows the computer to play back the transition at full speed and quality.

To preview the transition, simply play the timeline by clicking Play under the preview window or pressing the space bar on your keyboard. If you don’t like the style of the transition, you can delete it by clicking the transition to select it, and then pressing Delete on your keyboard.

Previewing transitions in Pinnacle Studio

Pinnacle Studio comes with 142 (yes, 142) transitions. In fact, so many transitions are provided with Studio that they don’t all fit on one page. To see a list of Studio’s transitions, click the Show Transitions tab on the left side of the album. There are several pages of transitions, and you can view additional pages by clicking the arrows in the upper-right corner of the album.

To preview a transition, simply click it in the album window. A preview of the transition will appear in the viewer window to the right of the album. A blue screen labeled “A” represents the outgoing clip, whereas the incoming clip is represented by the orange “B” clip.

Reviewing iMovie’s transitions

Apple iMovie offers a selection of 13 transitions from which to choose. That may not sound like a big number, but I think you’ll find that iMovie’s 13 transitions cover the styles you’re most likely to use anyway. To view the transitions that are available in iMovie, click the Trans button above the Timeline.

As you look at the list of transitions, most of the names probably look pretty foreign to you. Names like “Circle Closing,” “Radial,” and “Warp Out” are descriptive, but really the only way to know how each transition will look is to preview it. To do so, click the name of a transition in the list. A small preview of the transition briefly appears in the transition preview window. Oops! You missed it. Click the transition’s name again. Wow, it sure flashes by quickly, doesn’t it? If you’d like to see a larger preview, click the Preview button. A full-size preview appears in iMovie’s main viewer screen. If your transition preview window shows nothing but a black screen when you click a transition, move the mouse pointer down and click a clip in the timeline or storyboard to select it. The selected clip should now appear when you preview a transition.

Choosing the best transition

When Windows Movie Maker first came out in 2000, choosing what type of transition to use between clips was easy because you only had two choices. You could either use a straight-cut transition (which is actually no transition at all) or a cross-fade/dissolve transition. If you wanted to use anything fancier, you were out of luck.

Thankfully, most modern video-editing programs — including Windows Movie Maker 2 — provide you with a pretty generous assortment of transitions. Transitions are usually organized in their own window or palette. Transition windows usually vary slightly from program to program, but the basics are the same.

How do you decide which transition is the best? The fancy transitions may look really cool, but I recommend restraint when choosing them. Remember that the focus of your movie project is the actual video content, not showing off your editing skills or the capabilities of your editing software. More often than not, the best transition is a simple dissolve. If you do use a fancier transition, I recommend using the same or a similar transition throughout your project. This will make the transitions seem to fit more seamlessly into the movie.

Friday, November 14, 2008

Using Fades and Transitions Between Clips

- Straight cut: This is actually no transition at all. One clips ends and the next begins, poof! Just like that.

- Fade: The outgoing clip fades out as the incoming clip fades in. Fades are also sometimes called dissolves.

- Wipe: The incoming clip wipes over the outgoing clip using one of many possible patterns. Alternatively, the outgoing clip may wipe away to reveal the incoming clip.

- Push: The outgoing clip is pushed off the screen by the incoming clip.

- 3-D: Some more advanced editing programs provide transitions that seem to work three dimensionally. For example, the outgoing clip might wrap itself up into a 3-D ball, which then spins and rolls off the screen. Pinnacle’s Hollywood FX plug-ins for Studio provide many interesting 3-D transitions. See Appendix D for more on Studio plug-ins.

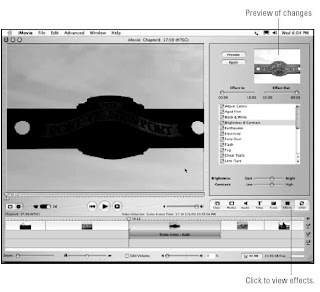

Modifying light and color in Apple iMovie

Although Apple iMovie doesn’t have specific image controls (as does, say, Studio), you can still modify color and light characteristics using some of iMovie’s effects. Start by selecting a clip that you want to adjust, and then click the Effects button in the upper-right portion of the timeline. The Effects window appears (as shown in Figure). Then you can use any of several effects to improve the appearance of the clip. Most effects have controls you can adjust by moving sliders. You can also control how the effect starts and finishes. Effects that can modify color and lighting include the following:

Although Apple iMovie doesn’t have specific image controls (as does, say, Studio), you can still modify color and light characteristics using some of iMovie’s effects. Start by selecting a clip that you want to adjust, and then click the Effects button in the upper-right portion of the timeline. The Effects window appears (as shown in Figure). Then you can use any of several effects to improve the appearance of the clip. Most effects have controls you can adjust by moving sliders. You can also control how the effect starts and finishes. Effects that can modify color and lighting include the following:- Adjust Colors: Allows you to adjust hue, saturation (color), and lightness.

- Aged Film: If the clip looks really bad, you can avoid blame by applying this effect to make it look like it’s from really old film. (“See, it’s not my fault that the colors are all wrong — this was shot on 8mm film 40 years ago!”) Your secret is safe with me. The Aged Film effect lets you adjust three different factors:

- The Exposure slider lets you make the aged effect appear lighter or darker.

- The Jitter slider controls how much the video image “jitters” up and down. Jitter makes the clip look like film that is not passing smoothly through a projector.

- The Scratches filter lets you adjust how many film “scratches” appear on the video image.

- Black & White: Converts the clip to a black and white image.

- Brightness & Contrast: Adjusts brightness and contrast in the image. (In Figure, I have increased brightness and contrast to improve the appearance of a backlit video clip.) Separate sliders let you control brightness and contrast separately.

- Sepia Tone: Gives the clip an old-fashioned sepia look.

- Sharpen: Sharpens an otherwise blurry image. A slider control lets you fine-tune the level of sharpness that is applied.

- Soft Focus: Gives the image a softer appearance, simulating the effect of a soft light filter on the camera. Three slider controls let you customize the Soft Focus effect:

- The Softness slider controls the level of softness. Move the Softness control towards the Lots end of the slider for a dreamsequence look.

- The Amount slider controls the overall level of the Soft Focus effect.

- The Glow slider increases or decreases the soft glow of the effect. Setting the Glow slider towards High tends to wash out the entire video clip.

Adjusting image qualities in Pinnacle Studio

Pinnacle Studio provides a pretty good selection of image controls. You can use these controls to improve brightness and contrast, adjust colors, or add a stylized appearance to a video image. To access the color controls, doubleclick a clip that you want to improve or modify. When the Clip Properties dialog box appears, click the Adjust Color or Add Visual Effects tab on the left side of the Clip Properties window. The Color Properties window appears as shown in Figure.

Pinnacle Studio provides a pretty good selection of image controls. You can use these controls to improve brightness and contrast, adjust colors, or add a stylized appearance to a video image. To access the color controls, doubleclick a clip that you want to improve or modify. When the Clip Properties dialog box appears, click the Adjust Color or Add Visual Effects tab on the left side of the Clip Properties window. The Color Properties window appears as shown in Figure.At the top of the Color Properties window is the Color Type menu. Here you can choose a basic color mode for the clip. The normal mode is All Colors, but you can also choose Black and White (shown in Figure), Single Hue, or Sepia. Below that menu are eight controls (listed in the order they appear) that you manipulate using sliders:

- Hue: Adjusts the color bias for the clip. Use this if skin tones or other colors in the image don’t look right.

- Saturation: Adjust the intensity of color in the image.

- Brightness: Makes the image brighter or darker.

- Contrast: Adjust the contrast between light and dark parts of the image. If the image appears too dark, use brightness and contrast together to improve the way it looks.

- Blur: Adds a blurry effect to the image.

- Emboss: Simulates a carving or embossed effect. It looks cool, but is of limited use.

- Mosaic: Makes the image look like a bunch of large colored blocks. This is another control you probably won’t use a whole lot.

- Posterize: Reduces the number of different colors in an image. Play with it; you might like it.

Adjusting playback speed in Pinnacle Studio

Pinnacle Studio gives you pretty fine control over playback speed. You can also adjust Strobe if you want to create a stop-motion effect that you may or may not find useful. The only way to really know is to experiment, which you can do by following these steps:

Pinnacle Studio gives you pretty fine control over playback speed. You can also adjust Strobe if you want to create a stop-motion effect that you may or may not find useful. The only way to really know is to experiment, which you can do by following these steps:- Switch to the timeline (if you’re not there already) by clicking the timeline view button (refer to Figure).

- Double-click a clip in the timeline to open the Clip Properties window.

- Click the Vary Playback Speed tool on the left side of the Clip Properties window (as in Figure). The Vary Playback Speed controls appear as shown in Figure.

- Move the Speed slider left to slow down the clip, or move it to the right to speed up the clip. An adjustment factor appears above the slider. Normal speed is shown as 1.0 X. Double speed would be 2.0 X, and so on. If you slow the playback speed down, a fraction will appear instead. For example, half speed will be indicated as 5/10 X.

- Move the Strobe slider to add some strobe effect.

- Click Play in the preview window to view your changes.

- If you don’t like your changes and want to revert to the original speed or strobe setting, click one of the Reset buttons.

- Click the Close (X) button in the upper-right corner of the Clip. Properties window when you’re done making changes.

Adjusting playback speed in Apple iMovie

Changing playback speed in iMovie couldn’t be easier. If you look closely, you’ll see a slider adjustment for playback speed right on the timeline. To adjust speed, follow these steps:

Changing playback speed in iMovie couldn’t be easier. If you look closely, you’ll see a slider adjustment for playback speed right on the timeline. To adjust speed, follow these steps:- Switch to the timeline (if you aren’t there already) by clicking the timeline view button (refer to Figure).

- Click the clip that you want to adjust to select it. The clip should turn blue when it is selected.

- Adjust the speed slider at the bottom of the timeline, as shown in Figure. To speed up the clip, move the slider toward the hare. Move the slider toward the tortoise to (surprise) slow down the clip.

- Play the clip to preview your changes.

- Giggle at the way the audio sounds after your changes.

Friday, October 31, 2008

Adjusting playback speed

One of the coolest yet most unappreciated capabilities of video-editing programs is the ability to change the speed of video clips. Changing the speed of a clip serves many useful purposes:

- Add drama to a scene by slowing down the speed to create a “slow-mo” effect.

- Make a scene appear fast-paced and action-oriented (or humorous, depending upon the subject matter) by speeding up the video.

- Help a given video clip better fit into a specific time frame by speeding it up or slowing it down slightly. For example, you may be trying to time a video clip to match beats in a musical soundtrack.

Undoing what you’ve done

Oops! If you didn’t really mean to delete that clip, don’t despair. Just like word processors (and many other computer programs), video-editing programs let you undo your actions. Simply press Ctrl+Z (Windows) or Ô+Z (Macintosh) to undo your last action. Both Pinnacle Studio and Apple iMovie allow you to undo several actions, which is helpful if you’ve done a couple of other actions since making the “mistake” you want to undo. To redo an action that you just undid, press Ctrl+Y (Windows) or Shift+Ô+Z (Macintosh). Another quick way to restore a clip in iMovie to its original state — regardless of how long ago you changed it — is to select the clip in the timeline and then choose Advanced➪Restore Clip. The clip reverts to its original state.

Removing clips from the timeline

Changing your mind about some clips that you placed in the timeline is virtually inevitable, and fortunately removing clips is easy. Just click the offending clip to select it and press the Delete key on your keyboard. Poof! The clip disappears.

If you’re using iMovie, you should know however that when you delete a clip by pressing the Delete key, the clip goes to iMovie’s trash bin. After the trash is emptied (by double-clicking the trash icon at the bottom of the iMovie program window), the deleted clip will no longer be stored on your hard drive, meaning that if you decide you want it back later, you’ll have to re-capture it. Thus, if you simply want to remove a clip from the timeline, I recommend that you first switch to the storyboard, and then drag the unwanted clip back up to the clip browser so you can use it again later if you want.

Sunday, October 19, 2008

Trimming clips in Apple iMovie

To trim a clip, follow these steps:

- Click a clip in the timeline to select it. When you click the clip, it should load into the preview window. If it does not, make sure that the desired clip is actually selected in the timeline. The clip should turn blue when it is selected.

- Click-and-drag the out-point marker in the lower-left corner of the preview window to a new location along the playback ruler.

- Click-and-drag the in-point marker to a new position if you wish. The selected portion of the clip — that is, the portion between the in and out points — will turn yellow in the preview window playback ruler.

- Choose Edit>Crop The clip will be trimmed (cropped) down to just the portion you selected with the in and out points. Subsequent clips in the timeline will automatically shift to fill in the empty space on the timeline. If you trim a video clip from which you have extracted the audio, only the video clip will be trimmed; you’ll have to trim the audio separately.

Trimming clips in Pinnacle Studio

The playback controls in the Clip Properties window include a Play Clip Continuously button. Click this button to preview the clip so it loops over and over continuously. This can help you better visualize the effects of any changes you make to the in and out points. When you’re done trimming the clip, click the Close (X) button in the upper

right corner of the Clip Properties window. The Clip Properties window closes and the length of your clip in the timeline will be changed accordingly.

Fine-Tuning Your Movie in the Timeline

After you’ve plopped a few clips into your timeline or storyboard, you’re ready to fine-tune your project. This fine-tuning is what turns your series of clips into a real movie. Most of the edits described in this section require you to work in the timeline, although if you want to simply move clips around without making any edits or changes, you’ll probably find that easiest in the storyboard. This is especially true if you’re using iMovie. To move a clip, simply click-and-drag it to a new location .

Dropping clips into the storyboard or timeline is a great way to assemble the movie, but a lot of those clips probably contain some material that you don’t want to use.

Monday, September 29, 2008

What did iMovie do with my audio?

extract the audio from each video clip individually. To do so, follow these steps:

- Click once on a clip in the timeline to select it.

- Choose Advanced➪Extract Audio, or press Ô+J. The audio will now appear as a separate clip in the timeline.

- Repeat Steps 1 and 2 for each clip in the timeline. It may be a good idea to wait until later (like, when you’re done editing the video portion of the movie) to extract audio from your video clips. If you still need to trim the video clip, you’ll have to trim the audio clip separately if it has been extracted

How to lock timeline tracks in Pinnacle Studio?

- Click the track header on the left side of the timeline. A lock icon appears on the track header, and a striped gray background is applied to that track.

- Perform edits on other tracks. For example, if you want to delete the audio track for one of your video clips, click the audio clip once to select it, and then press Delete on your keyboard. The audio portion of the clip disappears, but the video clip remains unaffected.

- Click the track header again to unlock the track. You can undo changes (such as deleting an audio clip) in Pinnacle Studio by pressing Ctrl+Z. If you followed the steps just given, press Ctrl+Z once to relock the track, and then press Ctrl+Z again to undelete the audio clip.

Saturday, September 13, 2008

Tracking timeline tracks

As you look at the timeline in your editing software, you’ll notice that it displays several different tracks. Each track represents a different element of the movie — video resides on the video track; audio resides on the audio track. You may have additional tracks available as well, such as title tracks or music.

Some advanced video-editing programs (such as Adobe Premiere and Final Cut Pro) allow you to have many separate video and audio tracks in a single project. This advanced capability is useful for layering many different elements and performing some advanced editing techniques. When you record and capture video, you usually capture audio along with it. When you place one of these video clips in the timeline, the accompanying audio appears just underneath it in the audio track. Seeing the audio and video tracks separately is important for a variety of editing purposes.

Zooming in and out on the timeline

Depending on how big your movie project is, you may find that clips on the timeline are often either too wide or too narrow to work with effectively. To rectify this situation, adjust the zoom level of the timeline. You can either zoom in and see more detail, or zoom out and see more of the movie. To adjust zoom, follow these steps:

- Apple iMovie: Adjust the Zoom slider control in the lower left corner of the timeline.

- Microsoft Windows Movie Maker: Click the Zoom In or Zoom Out magnifying glass buttons above the timeline, or press Page Down to zoom in and Page Up to zoom out.

- Pinnacle Studio: Press the + key to zoom in, or press the - key to zoom out. Alternatively, hover your mouse pointer over the timeline ruler so the pointer becomes a clock, and then click-and-drag left or right on the ruler to adjust zoom.

Using the timeline

Some experienced editors prefer to skip the storyboard and go straight to the timeline because it provides more information and precise control over your movie project. To switch to the timeline, click the timeline button.

One of the first things you’ll probably notice about the timeline is that not all clips are the same size. In the timeline view, the width of each clip represents the length (in time) of that clip, unlike in storyboard view, where each clip appears to be the same size. In timeline view, longer clips are wider, shorter clips are narrower.

Adding a clip to the timeline is a lot like placing clips in the storyboard. Just use drag-and-drop to move clips from the clip browser to the timeline. Clips that fall after the insert are automatically shifted over to make room for the inserted clip.

Visualizing your video project with storyboards

If you’ve ever watched a “making of” documentary for a movie, you’ve probably seen filmmakers working with a storyboard. It looks like a giant comic strip where each panel illustrates a new scene in the movie. The storyboard in your video-editing program works the same way. You can toss scenes in the storyboard, move them around, remove scenes again, and just generally put your clips into the basic order in which you want them to appear in the movie. The storyboard is a great place to visualize the overall concept and flow of your movie.

To add clips to the storyboard, simply drag them from the clip browser down to the storyboard at the bottom of the screen.

The storyboard should show a series of thumbnails. If your screen doesn’t quite look like this, you may need to switch to the storyboard view. The storyboard is possibly one of the most aptly named items in any videoediting program because the thumbnails actually do tell the basic story of your movie. The storyboard is pretty easy to manipulate. If you don’t like the order of things, just click-and-drag clips to new locations. If you want to remove a clip from the storyboard in iMovie, Studio, or most any other editing program, click the offending clip once to select it and then press Delete on your keyboard.

Turning Your Clips into a Movie

- Storyboard: This is where you throw clips together in a basic sequence from start to finish — think of it as a rough draft of your movie.

- Timeline: After your clips are assembled in the storyboard, you can switch over to the timeline to fine-tune the movie and make more advanced edits. The timeline is where you apply the final polish.

Wednesday, August 27, 2008

Understanding timecode

A video image is actually a series of still frames that flash rapidly by on-screen. Every frame is uniquely identified with a number called a timecode. All stored locations and durations of all the edits you perform on a movie project use timecodes for reference points, so a basic understanding of timecode is important. You’ll see and use timecode almost every time you work in a video-editing program like Pinnacle Studio or Apple iMovie. Timecode is often expressed like this:

hours : minutes : seconds :frames

The fourteenth frame of the third second of the twenty-eighth minute of the first hour of video is identified as:

01:28:03:13

You already know what hours, minutes, and seconds are. Frames aren’t units of time measurement, but rather, the individual still images that make up your video. The frame portion of timecode starts with zero (00) and counts up to a number determined by the frame rate of the video. In PAL video, frames are counted from 00 to 24 because the frame rate of PAL is 25 frames per second (fps). In NTSC, frames are counted from 00 to 29. The NTSC and PAL video standards are described in greater detail in Chapter 3. “Wait!” you exclaim. “Zero to 29 adds up to 30, not 29.97.”

You’re an observant one, aren’t you? As mentioned in Chapter 3, the frame rate of NTSC video is 29.97 fps. NTSC timecode actually skips the frame codes 00 and 01 in the first second of every minute, except every tenth minute. Work it out (you may use a calculator), and you see that this system of reverse leap-frames adds up to 29.97 fps. This is called drop-frame timecode. In some video-editing systems, drop-frame timecode is expressed with semicolons (;) between the numbers instead of colons (:).

Thus, in drop-frame timecode, the fourteenth frame of the third second of the twenty-eighth minute of the first hour of video is identified as

01;28;03;13

Why does NTSC video use drop-frame timecode? Back when everything was broadcast in black and white, NTSC video was an even 30 fps. For the conversion to color, more bandwidth was needed in the signal to broadcast color information. By dropping a couple of frames every minute, there was enough room left in the signal to broadcast color information, while at the same time keeping the video signals compatible with older black-and-white TVs.

Although the punctuation (for example, colons or semicolons) for separating the numerals of timecode into hours, minutes, seconds and frames is fairly standardized, some videoediting programs still go their own way. Pinnacle Studio, for example, uses a decimal point between seconds and frames. But whether the numbers are separated by colons, decimals, or magic crystals, the basic concept of timecode is the same.

Trimming out the unwanted parts

Professional Hollywood moviemakers typically shoot hundreds of hours of footage just to get enough acceptable material for a two-hour feature film. Because the pros shoot a lot of “waste” footage, don’t feel so bad if every single frame of video you shot isn’t totally perfect either. As you preview your clips, you’ll no doubt find bits that you want to cut from the final movie. The subject scratches his lip for a few moments at the beginning of the clip, which would be fine, except that it kind of looks like he’s picking his nose. We can’t have that in the final movie. Besides, the clip is about 11 seconds long, and we really only need about five seconds or so.

The solution is to trim the clip down to just the portion you want. The easiest way to trim a clip is to split it into smaller parts before you place it in your movie project:

- Open the clip you want to trim by clicking it in the browser, and move the play head to the exact spot where you want to split the clip. Use the playback controls under the preview window to move the play head. If you’re using the Scene 2 sample clip, place the play head about four seconds into the clip. If you’re using Pinnacle Studio, the timecode will actually read about 0:00:16.20 because the timecode is for the entire sample file and not just the selected clip.

- In Pinnacle Studio, right-click the clip in the browser and choose Split Scene from the menu that appears. In Apple iMovie, choose Edit➪Split Video Clip at Playhead. You now have two clips where before you had only one.

- To split the second clip again, choose the second clip by clicking it in the browser and move the play head about five seconds forward in the clip. Again, in Pinnacle Studio the timecode will actually read about 0:00:21.20 because the timecode displayed is for the entire sample file.

- Repeat Step 2 to split the clip again. You will now have three clips created from the one original clip. Splitting clips like I’ve shown here isn’t the only way to edit out unwanted portions of video. You can also trim clips once they’re placed in the timeline of your movie project. But splitting the clips before you add them to a project is often a much easier way to work because the unwanted parts are split off into separate clips that you can use (or not use) as you wish. In the next section, I show you how to add clips to the timeline or storyboard of your editing program to actually start turning your clips into a movie.

Don’t worry! Trimming a clip doesn’t delete the unused portions from your hard drive. When you trim a clip, you’re actually setting what the video pros call in points and out points. The software uses virtual markers to remember which portions of the video you chose to use during a particular edit. If you want to use the remaining video later, it’s still on your hard drive, ready for use. If you want, you can usually unsplit your clips that you have split as well. In Pinnacle Studio, hold down the Ctrl key and click on each of the clips that you split earlier.

When each clip is selected, right-click the clips and choose Combine Scenes. Unfortunately, Apple iMovie doesn’t have a simple tool for recombining clips that you have split. If you just split a clip, you can undo that action by choosing Edit➪Undo or pressing Ô+Z.

Previewing clips

As you gaze at the clips in your clip browser, you’ll notice that a thumbnail image is shown for each clip. This thumbnail usually shows the first frame of the clip; although it may suggest the clip’s basic content, you won’t really know exactly what the clip contains until you actually preview the whole thing. Previewing a clip is easy: Just click your chosen clip in the browser, and then click the Play button in the playback controls of your software’s preview window.

As the clip plays, notice that the play head under the preview window moves. You can move to any portion of a clip by clicking-and-dragging the play head with the mouse.

As you preview clips and identify portions you want to use in your movies, you’ll find precise, frame-by-frame control of the play head is crucial. The best way to get that precision is to use keyboard buttons instead of the mouse. If you’re using different editing software, check the manufacturer’s documentation for keyboard controls.

As you can see, some controls are fairly standardized across many different video-editing applications. In fact, the Spacebar also controls the Play/Stop/Pause function in professional-grade video editors like Adobe Premiere and Apple Final Cut Pro.

If you don’t like using the keyboard to try to move to just the right frame, you may want to invest in a multimedia controller such as the SpaceShuttle A/V from Contour A/V Solutions (www.contouravs.com). This device connects to your computer’s USB port and features a knob and dial that you can use to precisely control video playback. It’s so much easier than using the mouse or keyboard, you’ll wonder how you ever got by without one!

Organizing clips

Virtually all video-editing software stores clips in a grid-like area called a clip browser or album. Apple iMovie and Pinnacle Studio further subdivide clips by content. Each program has separate browser panels for video clips, audio clips, and still images. In Studio, you can access these panels using tabs along the left side of the clip browser or album, as it is called in Pinnacle’s documentation. In iMovie, you can access the panels using buttons at the bottom of the clip browser or pane, as Apple’s documentation calls it.

The clip browser doesn’t just store your clips, it also tells you some important information about them. One of the most important bits of info is the length of the clip. If you’re using the sample clips from the CD-ROM, you’ll notice the numerals 19.04 or 19:04 next to Scene 5. This tells you that the clip is 19 seconds and four frames long. If you don’t see names or lengths listed next to clips in the Studio clip browser, choose Album➪Details View. A video image is actually made up of a series of still images that flash by so quickly that they create the illusion of motion. These still images are called frames. Video usually has about 30 frames per second. The clip also has a name, of course, and you can change the name if you wish. If, for example, you think that “Bridge” would be a more descriptive name than “Scene 5,” click the clip once, wait a second, and then click the clip’s name once again. You can then type a new name if you want. When you’re done typing a new name, just press Enter or click in an empty part of the screen.

If you have a lot of clips in the browser, they might not all fit on one screen. In iMovie, simply scroll down (using the scroll bar on the right) to see more clips. In Pinnacle Studio, you can select different groups of clips from the menu at the top of the browser. If there are too many clips in a group to fit on a single page all at once, you can click the arrows to view additional pages.

In iMovie’s clip browser, you can manually rearrange clips by dragging them to new empty blocks in the grid. You can move the clips wherever you want. This handy feature allows you to sort clips on your own terms, rather than just have them listed alphabetically or in some other arbitrary order.

Friday, August 15, 2008

Working with Clips

As you make movies, you’ll quickly find that “clip” is the basic denomination of the media that you work with. You’ll spend a lot of time with video clips, audio clips, and even still clips (you know, those things that used to be called “pictures” or “photos”).

A still clip usually consists of a single picture; an audio clip usually consists of a single song or sound effect; and a video clip usually consists of a single scene. A scene most often starts when you press the Record button on your camcorder, and ends when you stop recording again, even if only for a second. When you import video from your camcorder, most video-editing programs automatically detect these scenes and create individual clips for you. As you edit and create your movies, you’ll find this feature incredibly useful.

Starting a New Editing Project

Your first step in working on any movie project is to actually create the new project. This step is pretty easy. In fact, when you launch your video-editing program, it will usually start with a new, empty project. But if you need to create a new project for some reason or just want to be sure that you’re starting from a clean slate, choose File➪New Project. No matter if you’re using Apple iMovie, Pinnacle Studio, or almost any other video-editing program —a new, empty project window should appear.

After you have a new project started, your first step is usually to capture or import some video so you have something to edit. If you have some video to capture. Captured video will appear as clips in the clips pane (in iMovie) or the Album (in Studio), where it will be ready to use in your movies.

If you don’t have any video of your own to import or capture right now, you can still practice editing using sample videos from the CD-ROM that accompanies this book. If you plan to use those sample clips, insert the disc into your CD-ROM drive. To import the sample clips using Pinnacle Studio on a PC, follow these steps:

- Click the Edit view mode tab or choose View➪Edit to ensure that you’re in Edit mode. If this is the first time you’ve used Studio, you’ll probably see the sample clips from Pinnacle’s Photoshoot sample movie.

- Click the Select Video Files button in the clip browser The generic Open File window common to virtually all Windows programs appears.

- Browse to the folder Samples\Chapter8.

- Choose the newport file and click Open. The file is imported; Studio should automatically detect five scenes in the movie. If you’re using a Mac, import the clips into iMovie by following these steps:

- Open iMovie and choose File➪Import. The generic Open File dialog box common to virtually all OS X programs appears.

- Browse to the folder Samples\Chapter8 on the CD-ROM.

- Click-and-drag over all five scene clips to select them and then click Open.

The five clips will be imported and will appear in the Clip browser. The Macintosh-compatible sample files on the CD are in Apple QuickTime format. If you’re using Apple iMovie, you need version 3 or higher of iMovie to import QuickTime-format video files.

After you have imported the clips, I recommend that you save and name the project by clicking File➪Save Project. Saving early is important because it not only preserves your work, but it is also required before you can perform certain editing tasks later on.

Basic Editing

But video editing . . . now, that’s cool. Until recently, high quality video productions with special effects, on-screen titles, and fancy transitions between scenes were magical productions made by pros using equipment that cost hundreds of thousands (if not millions) of dollars. But thanks to the dual revolutions of digital camcorders and powerful personal computers, all you need for pro-quality video production is a computer, a digital camcorder, a little cable to connect them both, and some software. Within just a few mouse clicks, you’ll be making movie magic!

Ripping MP3 files in Windows

As I mention earlier, the process of turning audio files into MP3 files is sometimes called encoding or ripping. Microsoft provides a free audio-player program called Windows Media Player — WMP for short. It comes with Windows, and you can download the latest version from www.windowsmedia.com. Like Apple’s iTunes for the Macintosh, WMP allows you to copy music from audio CDs to your hard drive in a high-quality (yet compact) format. Unfortunately, as delivered, WMP does not rip files in MP3 format. Instead, it uses the Windows Media Audio (WMA) format.

Windows Media files are about as small as MP3 files, but it’s a proprietary format: Most video-editing programs (including Pinnacle Studio) cannot import WMA files directly. If you want to import music from CDs into a Studio movie project, it’s better to copy the music directly from within Studio.

If you really want to be able to copy music onto your hard drive in MP3 format, you’ll have to obtain commercially available MP3 encoding software. Such programs are available at most electronics stores, and you can also download software from Web sites such as www.tucows.com. I use a tool called CinePlayer from Sonic Solutions (www.cineplayer.com). This $20 tool works as a plug-in for Windows Media Player in Windows XP, and allows WMP to both encode MP3 files and play DVD movies. After it’s installed, I simply open Windows Media Player and choose Tools➪Options.

Then, on the Copy Music tab of the Options dialog box,

I can choose MPEG Layer-3 Audio in the Format drop-down box, and adjust quality settings as I see fit. The MPEG Layer-3 option is available here only because I have the CinePlayer plug-in installed. With these settings, WMP uses the MP3 format instead of WMA when I copy music to my hard disk.

How to Rip MP3 files on a Mac?

The process of turning an audio file into an MP3 file is sometimes called ripping or encoding. Apple has thoughtfully provided the capability to create MP3 files with its free audio-library-and-player program, iTunes. To download the latest version of iTunes, visit www.apple.com/itunes/ and follow the instructions there. After iTunes is installed on your computer, copying audio onto your hard drive in MP3 format is quite simple:

- Insert an audio CD into your CD-ROM drive.

- If iTunes doesn’t launch automatically, open the program using the Dock or your Applications folder.

- With the iTunes program window active choose iTunes➪Preferences. The iTunes Preferences dialog box opens.

- Click the Importing button at the top of the Preferences dialog box.

- Make sure that MP3 Encoder is selected in the Import Using menu, and then click OK. The iTunes Preferences dialog box closes and you are returned to the main iTunes window.

- Place check marks next to the songs you want to import. You can use the playback controls in the upper-left corner of the iTunes window to preview tracks.

- Click Import in the upper right corner of the iTunes screen.The songs are imported; the process may take several minutes. When it’s done, the imported songs are available through your iTunes library for use in iMovie projects.

Working with MP3 Audio

MP3 is one of the most common formats for sharing audio recordings today. MP3 is short for MPEG Layer-3, and MPEG is short for Motion Picture Experts Group, so really you can think of MP3 as an abbreviation of an abbreviation. I’m sure that in a few years an MP3 file will simply be called an “M” or “P” (or maybe even a “3”) file — but whatever their collective nickname, MP3 audio files are likely to remain popular.

The MP3 file format makes for very small files — you can easily store a lot of music on a hard drive or CD — and those files are easy to transfer over the Internet. Who am I kidding? You probably already know all about MP3 files. You might even have some MP3 files already stored on your computer. If so, using those MP3 files for background music in your movie projects is really easy:

- In iMovie: Pull MP3 files directly from your iTunes library into iMovie, using the procedure described earlier in this chapter for importing CD Audio. Simply choose iTunes from the pull-down menu at the top of the audio pane.

- In Studio: Choose Album➪Sound Effects to show the sound-effects album. Click the folder icon and browse to the folder on your hard drive that contains the MP3 files you want to use.

Tuesday, July 29, 2008

Understanding music copyrights

Music can easily be imported into your computer for use in your movies. The tricky part is obtaining the rights to use that music legally. Realistically, if you’re making a video of your daughter’s birthday party, and you only plan to share that video with a grandparent or two, Kool and the Gang probably don’t care if you use the song “Celebration” as a musical soundtrack. But if you start distributing that movie all over the Internet — or (even worse) start selling it — you could have a problem that involves the band, the record company, and lots and lots of lawyers.

The key to using music legally is licensing. You can license the right to use just about any music you want, but it can get expensive. Licensing “Celebration” for your movie project (for example) could cost hundreds of dollars or more. Fortunately, more affordable alternatives exist.

Numerous companies offer CDs and online libraries of stock audio and music, which you can license for as little as $30 or $40. You can find these resources by searching the Web for “royalty free music,” or visit a site such as www.royaltyfree.com or www.royalty freemusic.com. You usually must pay a fee to download or purchase the music initially, but after you have purchased it, you can use the music however you’d like. If you use audio from such a resource, make sure you read the licensing agreement carefully. Even though the music is called “royalty free,” you still may be restricted on how many copies you may distribute, how much money you can charge, or what formats you may offer.

Another — more affordable — alternative may be to use the stock audio that comes with some moviemaking software. Pinnacle Studio, for example, comes with a tool called SmartSound which automatically generates music in a variety of styles and moods. Although you should always carefully review the software license agreements to be sure, normally the audio that comes with moviemaking software can be used in your movie projects free of royalties.

How to Import CD audio in Pinnacle Studio?

Pinnacle Studio provides an audio toolbox to help you work with CD audio and other formats. To open the audio toolbox in Studio, place an audio CD in your CD-ROM drive and choose Toolbox➪Add CD Music. You may be asked to enter a title for the CD. The exact title doesn’t matter, so long as it’s something you will be able to identify and remember later. The audio toolbox allows you to perform a variety of actions:

- Choose audio tracks from the CD using the Track menu.

- Use playback controls in the audio toolbox to preview audio tracks.

- Add only a portion of the audio clip to your movie by adjusting the in point and out point markers.

- Add a track to the movie as a clip in the background music track at the bottom of the timeline by clicking the Add to Movie.

How to Import CD audio in iMovie?

If you’re using Apple iMovie, you can take audio directly from your iTunes library or import audio from an audio CD. Here’s the basic drill:

- Put an audio CD in your CD-ROM drive, and then click the Audio button above the timeline on the right side of the iMovie screen. The audio pane appears.

- If iMovie Sound Effects are currently shown, open the pull-down menu at the top of the audio pane and choose Audio CD. A list of audio tracks appears.

- Select a track and click Play in the audio pane to preview the song.

- Click Place at Playhead in the Audio panel to place the song in the timeline, beginning at the current position of the play head.

Recording voice-over tracks in Pinnacle Studio

Recording audio in Windows is pretty easy. Most video-editing programs —including Pinnacle Studio and Windows Movie Maker — give you the capability to record audio directly in the software. Before you can record audio, however, your computer must have a sound card and a microphone. (If your computer has speakers, it has a sound card.) The sound card should have a connector for a microphone as well. Check the documentation for your computer if you can’t find the microphone connector.

After your hardware is set up correctly, you’re ready to record audio in Pinnacle Studio or most any other movie making program. To record audio in Studio, follow these steps:

- Open the movie project for which you want to record audio, and switch to the timeline view if you aren’t there already.

- If you’re working with a current movie project, move the play head to the spot where you want to begin recording.

- Choose Toolbox➪Record Voice-over. The voice-over recording studio appears.

- Say a few words to test the audio levels. As your microphone picks up sound, the audio meter in Studio should indicate the recording level. If the meter doesn’t move at all, your microphone probably isn’t working. You’ll notice that as sound levels rise, the meter changes from green to yellow and finally red. For best results, try to keep the sound levels in or near the yellow part of the meter. You can fine-tune the levels by adjusting the Recording Volume slider.

- Click Record. A visible three-second countdown appears in the recording-studio window, giving you a couple of seconds to get ready.

- When recording begins and your movie project starts to play, recite your narration.

- When you’re done, click Stop.

Tuesday, July 15, 2008

How to do recording in iMovie?

Once you’ve decided which microphone to use and you’ve configured it as described in the previous section, you’re ready to record audio using iMovie.

As with most tasks in iMovie, recording is pretty easy:

- Open the project for which you want to record narration or other sounds, and switch to the timeline view if you’re not there already.

- If you’re working with a current movie project, move the play head to the spot where you want to begin recording.

- Click the Audio button above the timeline to open the audio pane.

- Say a few words to test the audio levels. As your microphone picks up sound, the audio meter in iMovie should indicate the recording level. If the meter doesn’t move at all, your microphone probably isn’t working. You’ll notice that as sound levels rise, the meter changes from green to yellow and finally red. For best results, try to keep the sound levels close to the yellow part of the meter. If the audio levels are too low, the recording may have a lot of unwanted noise relative to the recorded voice or sound. If levels are too high, the audio recording could pop and sound distorted. Unfortunately, iMovie doesn’t offer an audio level adjustment for audio you record, so you’ll have to fine-tune levels the old fashioned way, by changing the distance between the microphone and your subject.

- Click Record and begin your narration. The movie project plays as you recite your narration.

- When you’re done, click Stop.

How to set up an external microphone in Macintosh?

Some microphones can connect to the USB port on your Mac. A USB microphone will be easier to use because your Mac will automatically recognize it and select the USB mic as your primary recording source. If your external microphone connects to the regular analog microphone jack — and your Mac already has a built-in mic — you may find that iMovie doesn’t recognize your external microphone. To correct this problem, you must adjust your system’s Sound settings:

- Open the System Preferences window by choosing Apple➪System Preferences.

- Double-click the Sound icon to open the Sound preferences dialog box.

- Click the Input tab to bring it to the front.

- Open the Microphone pull-down menu and choose External Microphone/Line In.

- Press Ô+Q to close the Sound dialog box and System Preferences.

Your external microphone should now be configured for use in iMovie

How to connect a tape player to your computer?

If you recorded audio onto an audio tape, you can connect the tape player directly to your computer and record from it just as if you were recording from a microphone. Buy a patch cable (available at almost any electronics store) with two male mini-jacks (standard small audio connectors used by most current headphones, microphones, and computer speakers). Connect one end of the patch cable to the headphone jack on the tape player and connect the other end to your computer’s microphone jack. The key, of course, is to have the right kind of cable. You can even buy cables that allow you to connect an old record player to your computer and record audio from your old LPs.

Once connected, you can record audio from the tape using the same steps described in the sections in this chapter on microphone recording. You’ll have to coordinate your fingers so that you press Play on the tape player and click Record in the recording software at about the same time. If the recording levels are too high or too low, adjust the volume control on the tape player.

Audio Recording Basic Tips

At some point, you’ll probably want to record some narration or other sound to go along with your movie project. Recording great-quality audio is no simple matter. Professional recording studios spend thousands or even millions of dollars to set up acoustically superior sound rooms. I’m guessing you don’t have that kind of budgetary firepower handy, but if you’re recording your own sound, you can get nearly pro-sounding results if you follow these basic tips:

- Use an external microphone whenever possible. The built-in microphones in modern camcorders have improved greatly in recent years, but they still present problems. They often record undesired ambient sound near the camcorder (such as audience members) or even mechanical sound from the camcorder’s tape drive. If possible, connect an external microphone to the camcorder’s mic input.

- Eliminate unwanted noise sources. If you must use the camcorder’s built-in mic, be aware of your movements and other things that can cause loud, distracting noises on tape. Problem items can include a loose lens cap banging around, your finger rubbing against the mic, wind blowing across the mic, and the swish-swish of those nylon workout pants you wore this morning.

- Control ambient noise. True silence is a very rare thing in modern life. Before you start recording audio, carefully observe various sources of noise. These could include your neighbor’s lawn mower, someone watching TV in another room, extra computers, and even the heating duct from your furnace or air conditioner. Noise from any (or all) of these things can reduce the quality of your recording.

- Try to minimize sound reflection. Audio waves reflect off any hard surface, which can cause echoing in a recording. Cover the walls, floor, and other hard surfaces with blankets to reduce sound reflection.

- Obtain and use a high-quality microphone. A good mic isn’t cheap, but it can make a huge difference in recording quality.

- Watch for trip hazards! In your haste to record great sound, don’t forget that your microphone cables can become a hazard on-scene. Not only is this a safety hazard to anyone walking by, but if someone snags a cable, your equipment could be damaged as well. If necessary, bring along some duct tape to temporarily cover cables that run across the floor.

Delving into bit depth

Another term you’ll hear bandied about in audio editing is bit depth. The quality of a digital audio recording is affected by the number of samples per second, as well as by how much information each sample contains. The amount of information that can be recorded per sample is the bit depth. More bits per sample mean more information — and generally richer sound. Many digital recorders and camcorders offer a choice between 12-bit and 16-bit audio; choose the 16-bit setting whenever possible. For some reason, many digital camcorders come from the factory set to record 12-bit audio. There is no advantage to using the lower setting, so always check your camcorder’s documentation and adjust the audio-recording bit depth up to 16-bit if it isn’t there already.

Understanding sampling rates

For over a century, humans have been using analog devices (ranging from wax cylinders to magnetic tapes) to record sound waves. As with video, digital audio recordings are all the rage today. Because a digital recording can only contain specific values, it can only approximate a continuous wave of sound; a digital recording device must “sample” a sound many times per second; the more samples per second, the more closely the recording can approximate the live sound (although a digital approximation of a “wave” actually looks more like the stairs on an Aztec pyramid). The number of samples per second is called the sampling rate. As you might expect, a higher sampling rate provides better recording quality. CD audio typically has a sampling rate of 44.1 kHz — that’s 44,100 samples per second — and most digital camcorders can record at a sampling rate of 48kHz. You will work with sampling rate when you adjust the settings on your camcorder, import audio into your computer, and export movie projects when they’re done.

Sunday, June 29, 2008

Understanding Audio

Consider how audio affects the feel of a video program. Honking car horns on a busy street; crashing surf and calling seagulls at a beach; a howling wolf on the moors — these sounds help us identify a place as quickly as our eyes can, if not quicker. If a picture is worth a thousand words, sometimes a sound in your movie is worth a thousand pictures.

What is audio? Well, if I check my notes from high-school science class, I get the impression that audio is produced by sound waves moving through the air. Human beings hear those sound waves such as condolence phrases being told, they make our eardrums vibrate. The speed at which a sound makes the eardrum vibrate is the frequency. Frequency is measured in kilohertz (kHz), and one kHz equals one thousand vibrations per second. (You could say it really hertz when your eardrums vibrate . . . get it?) A lower-frequency sound is perceived as a lower pitch or tone, and a higher-frequency sound is perceived as a high pitch or tone. The volume or intensity of audio is measured in decibels (dB).

Capturing your video

- Click the Start Capture button at the bottom of the Studio capture window. The Capture Video dialog box appears.

- Enter a descriptive name for the capture.

- If you want to automatically stop capturing after a certain period of time, enter the maximum number of minutes and seconds for the capture.

- Press Play on the VCR or camcorder.

- Click Start Capture within the Capture Video dialog box. The capture process begins, and you’ll notice that the green Start Capture button changes to the red Stop Capture button. As Studio captures your video, keep an eye on the Frames Dropped field under the preview window. If any frames are dropped, try to determine the cause and then recapture the video. Common causes of dropped frames include programs running in the background, power saver modes, or a hard disk that hasn’t been defragmented recently.

- Click Stop Capture when you’re done capturing.

Adjusting video-capture settings in Studio

To make sure Studio is ready to capture analog video instead of digital video, click the Settings button at the bottom of the capture window. The Pinnacle Studio Setup Options dialog box appears. Click the Capture Source tab to bring it to the front. On that tab, review the following settings:

- Video: Choose your analog capture source in this menu. The choices in the menu will vary depending upon what hardware you have installed.

- Audio: This menu should match the Video menu.

- Use Overlay and Capture Preview: I recommend that you leave both these options disabled. Leaving these options on may cause dropped frames (that is, some video frames are missed during the capture) on some computers.

- Scene detection during video capture: This setting determines when a new scene is created. For most purposes, I recommend choosing “Automatic based on video content” for analog capture.

- Data rate: This section tells you how fast your hard disk can read or write. Click the Test Data Rate button to get a current speed estimate. Ideally, both numbers should be higher than 10,000 kilobytes per second for analog capture. If your system can’t reach that speed.

Now press Play on your VCR or camcorder to begin playing the video you plan to capture, but don’t start capturing it yet. As you play the analog video, watch the picture in the preview screen in the upper right corner of the Studio program window. If you don’t like the picture quality, you can use the brightness, contrast, sharpness, hue, and color saturation sliders on the Video Input control panel to adjust the picture. Experiment a bit with the settings to achieve the best result.

As you play your analog tape, you’ll probably notice that although you can see the video picture in the preview window, you can’t hear the sound through your computer’s speakers. That’s okay. Keep an eye on the audio meters on the Audio Capture control panel. They should move up and down as the movie plays. Ideally, most audio will be in the high green or low yellow portion of the audio meters. Adjust the audio-level slider between the meters if the levels seem too high or too low. If the audio seems biased too much to the left or right, adjust the balance slider at the bottom of the control panel. If you’re lucky, the tape you’re going to capture from has color bars and a tone at the beginning or end. In that case, use the bars and tone to calibrate your video picture and sound. The tone is really handy because it’s a standard 1KHz (kilohertz) tone designed specifically for calibrating audio levels. Adjust the audio-level slider so both meters read just at the bottom of the yellow. When you’re done playing with the settings in the Video and Audio control panels, stop the tape in your VCR or camcorder and rewind it back to where you want to begin capturing.

Using a video converter

Video converters are kind of neat because they don’t require you to break out the tools and open up your computer case. As their name implies, video converters convert analog video of your visit in Aztec ruins to digital before it even gets inside your computer.

The converter has connectors for your analog VCR or camcorder, and it connects to your computer via the FireWire port. Converters are available at many electronics retailers for about $200. Common video converters include

- Canopus ADVC-50: www.canopuscorp.com

- Data Video DAC-100: www.datavideo-tek.com

- Dazzle Hollywood DV Bridge: www.dazzle.com

If you have a digital camcorder, you might be able to use it as a video converter for analog video. Digital camcorders have analog connectors so you can hook them up to a regular VCR. Hook up a VCR to the camcorder, set up the camcorder and your computer for digital capture, and push play on the VCR. If the video picture from the VCR appears on the capture-preview screen on your computer, you can use this setup to capture analog video. This should work without having to first record the video onto tape in your digital camcorder, which means that using your camcorder as a converter won’t cause increased wear on the camcorder. Alas, some camcorders won’t allow analog input while a FireWire cable is plugged in. You’ll have to experiment with your own camera to find out if this method will work.